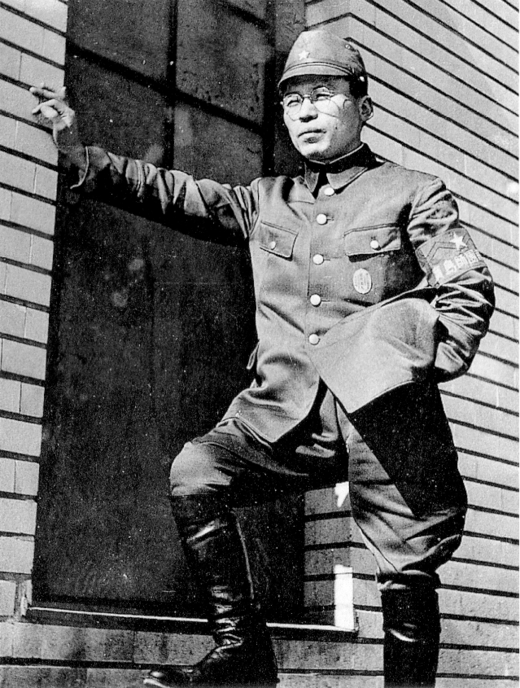

Yoshito Matsushige 松重美人

Yoshito Matsushige 松重美人

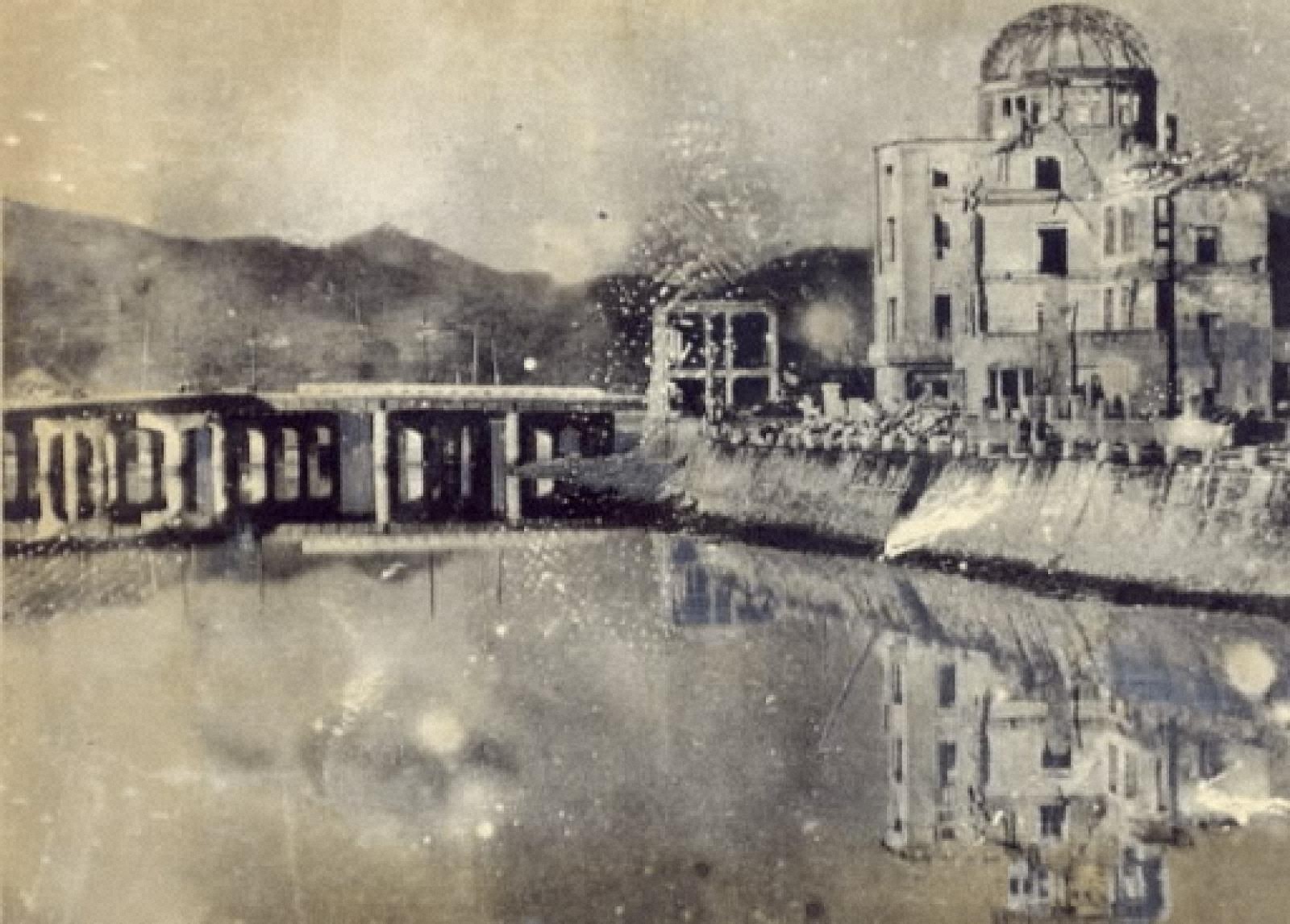

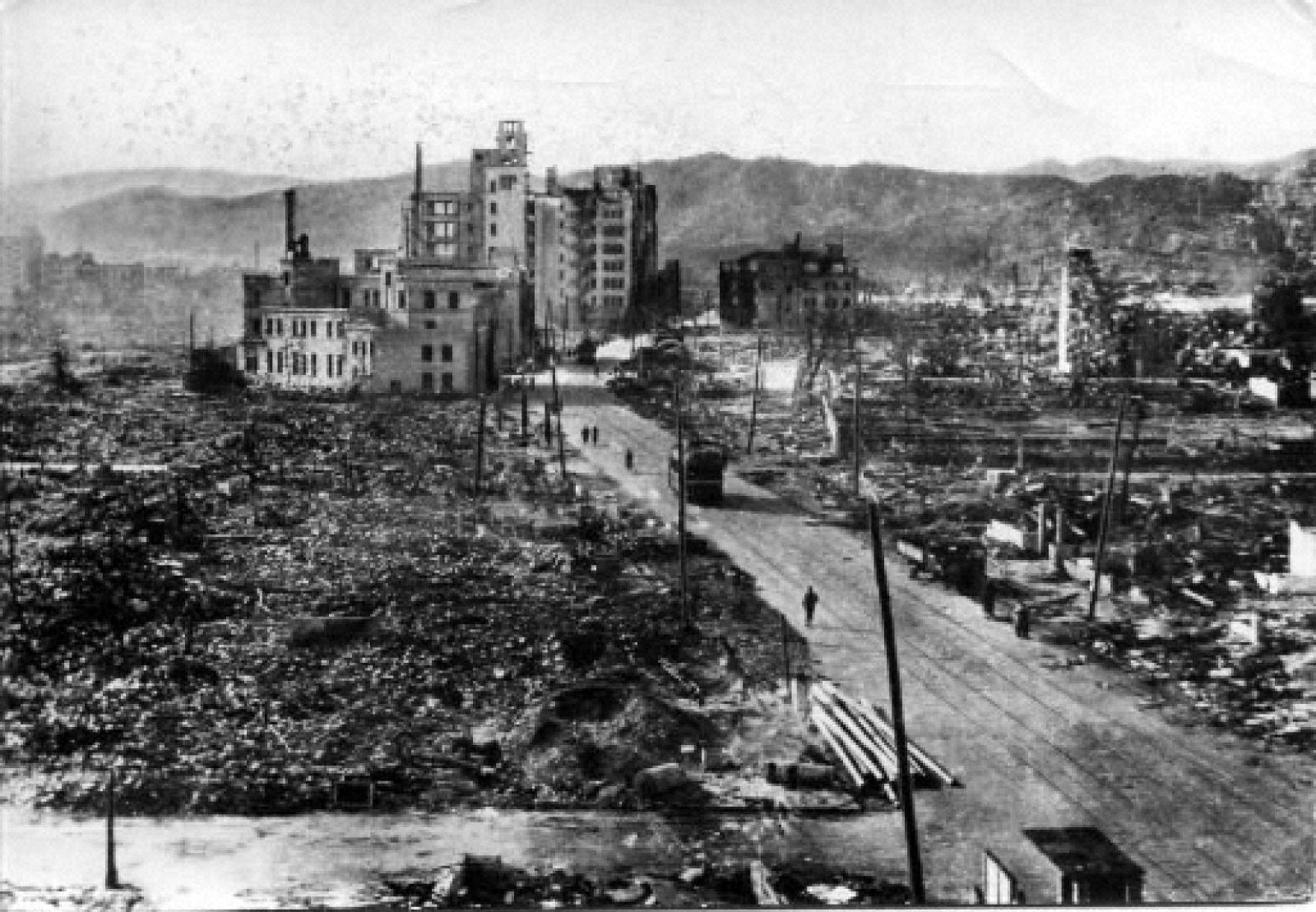

(1913-2005) is best known for being the only person to capture an immediate, first-hand photographic historical account of the destruction of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Matsushige joined Geibinichinichi Newspaper Corporation in 1941. After the company was merged with the Chugoku Shimbun Company, he was assigned to the photography department. After 1944, he also worked as a press report group member at Chugoku Regional Military Headquarters. Yoshito Matsushige was 32 years old at the time of the atomic bombing.Matsushige was home at the time of the atomic bombing. His home was located at Midori-cho, 1.7 miles from ground zero (hypocenter) of the explosion. This was just outside of the 1.5 mile radius of total destruction created by the atomic blast effects. Miraculously, Matsushige was not seriously injured by the explosion and was given one of the most famous photographic opportunities in human history. With one camera and two rolls of film (24 possible exposures) he tried to get his newspaper office but flames blocked his way.Matsushige returned to the Miyuki Bridge.

He tried to take photographs of the terrible carnage he witnessed at the bridge but could not press the shutter button. After struggling at that location for over thirty minutes, he finally took his first photographs. During the next ten hours Matsushige was only able to click the shutter seven times because the sights were so atrocious and heart-breaking to witness. In addition, he was afraid the burned and battered people would be enraged if someone took their pictures. Matsushige could not develop the film right away but eventually did so after twenty days, in the open, at night, using a radioactive stream to rinse the photographs. Only five of the seven photographs were developable.

A few weeks after the atomic bombing, the American military confiscated all of the post-bombing newspaper photographs and/or newsreel footage but failed to confiscate many of the negatives. As a result, photographs from the Hiroshima atomic bombing were not published until the United States occupation of Japan ended in April 1952. The magazine Asahi Gurafu initially published Matsushige’s photographs in a special edition on August 6, 1952. This edition was titled: “First Exposè of A-Bomb Damage”. This special edition sold out so quickly that four additional printings were run replacing the original color cover with a black and white one. The total circulation of this special edition was approximately 700,000. The following month, Life Magazine published two of the five Matsushige’s photographs in the September 29, 1952 edition of the magazine in an article titled: “When Atom Bomb Struck – Uncensored”.After retiring from the Chugoku Shimbun in 1969, Matsushige became a dedicated peace activist. He communicated his experience of witnessing the destruction and horrors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima through a series of photo essays and publishing several books. He gave speeches in Japan and abroad, including the United Nations General Assembly.

In 1978, Matsushige together with others who took photographs of the atomic bombing formed the Association of Photographers of the Atomic (Bomb) Destruction of Hiroshima. This organization included the families of those atomic bomb photographers who had passed away since 1945. Matsushige dedicated most of his life to the organization and preservation of the photo history of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Yoshito Matsushige Account of the Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima Japan:

I had finished breakfast and was getting ready to go to the newspaper when it happened. There was a flash from the indoor wires as if lightening had struck. I didn’t hear any sound, how shall I say, the world around me turned bright white. And I was momentarily blinded as if a magnesium light had lit up in front of my eyes. Immediately after that, the blast came. I was bare from the waist up, and the blast was so intense, it felt like hundreds of needles were stabling me all at once. The blast grew large holes in the walls of the first and second floor. I could barely see the room because of all the dirt. I pulled my camera and the clothes issued by the military headquarters out from under the mound of the debris, and I got dressed. I thought I would go to either the newspaper or to the headquarters. That was about 40 minutes after the blast. Near the Miyuki Bridge, there was a police box. Most of the victims who had gathered there were junior high school girls from the Hiroshima Girls Business School and the Hiroshima Junior High School No.1.

They had been mobilized to evacuate buildings and were outside when the bomb fell. Having been directly exposed to the heat rays, they were covered with blisters, the size of balls, on their backs, their faces, their shoulders and their arms. The blisters were starting to burst open and their skin hung down like rugs. Some of the children even have burns on the soles of their feet. They’d lost their shoes and run barefoot through the burning fire. When I saw this, I thought I would take a picture and I picked up my camera. But I couldn’t push the shutter because the sight was so pathetic. Even though I too was a victim of the same bomb, I only had minor injuries from glass fragments, whereas these people were dying. It was such a cruel sight that I couldn’t bring myself to press the shutter. Perhaps I hesitated there for about 20 minutes, but I finally summoned up the courage to take one picture. Then, I moved 4 or 5 meters forward to take the second picture. Even today, I clearly remember how the view finder was clouded over with my tears. I felt that everyone was looking at me and thinking angrily, “He’s taking our picture and will bring us no help at all.” Still, I had to press the shutter, so I harden my heart and finally I took the second shot. Those people must have thought me duly cold-hearted. Then, I saw a burnt streetcar which had just turned the corner at Kamiya-cho. There were passengers still in the car. I put my foot onto the steps of the car and I looked inside.

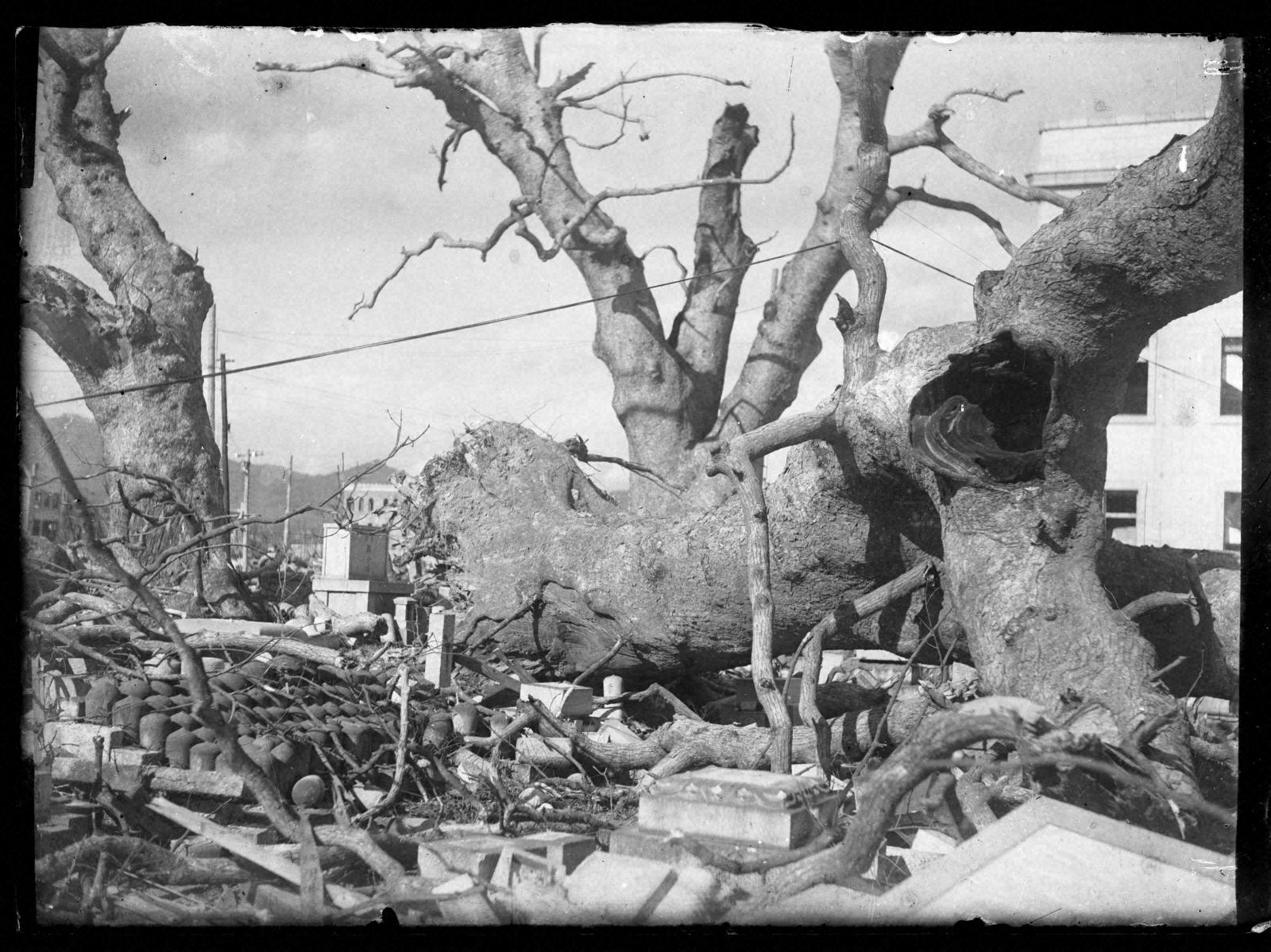

There were perhaps 15 or 16 people in front of the car. They laid dead one on top of another. Kamiya-cho was very close to the hypocenter, about 200 meters away. The passengers had stripped them of all their clothes. They say that when you are terrified, you tremble and your hair stands on end. And I felt just this tremble when I saw this scene. I stepped down to take a picture and I put my hand on my camera. But I felt so sorry for these dead and naked people whose photo would be left to posterity that I couldn’t take the shot. Also, in those days we weren’t allowed to publish the photographs of corpses in the newspapers. After that, I walked around, I walked through the section of town which had been hit hardest. I walked for close to three hours. But I couldn’t take even one picture of that central area. There were other cameramen in the army shipping group and also at the newspaper as well. But the fact that not a single one of them was able to take pictures seems to indicate just how brutal the bombing actually was. I don’t pride myself on it, but it’s a small consolation that I was able to take at least five pictures. During the war, air-raids took place practically every night. And after the war began, there were many foods shortages. Those of us who experienced all these hardships, we hope that such suffering will never be experienced again by our children and our grandchildren. Not only our children and grandchildren, but all future generations should not have to go through this tragedy. That is why I want young people to listen to our testimonies and to choose the right path, the path which leads to peace.

Hiroshima, August 6, 1945

Hiroshima, Subsequent photographs